The production of pasta in Gragnano dates back to the end of the 16th century when the first family-run pasta factories appeared in the area. History dates the origin of Gragnano's fame as the home of pasta manufacturing to 12 July 1845, the day on which the King of the Kingdom of Naples, Ferdinand II of Bourbon, during a lunch granted the Gragnano manufacturers the high privilege of supplying the Court of all long pastas. Since then Gragnano became the City of Macaroni.

In reality, the tradition of pasta making in Gragnano has very distant origins, which take us back to Roman times. Already at that time in the Gragnano area, wheat was being ground: the waters of the Vernotico stream, which flowed down the so-called Valle dei Mulini, operated the blades that grinded the crops arriving by sea from the Roman colonies. The flours thus obtained were then transformed into the bread that was to feed the neighboring cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae.

Over time, the need for the poor classes to have a minimum of food stocks gave rise to a new production, that of dry pasta, made with durum wheat semolina ground in the area. This activity quickly became such an important and deep-rooted tradition that in the 16th century the guild of "vermicellari" was established in Naples and in the same period an edict of the King of Naples conferred the license of vermicellaro to a Gragnanese. Until the seventeenth century it was a little widespread food, but following the famine that hit the Kingdom of Naples, it became a fundamental food thanks to its nutritional qualities and to the invention that allowed to produce pasta, called white gold, at low cost by pressing the dough through the dies. The ideal soils to allow the production were Gragnano and Naples, thanks to their microclimate composed of wind, sun and the right humidity.

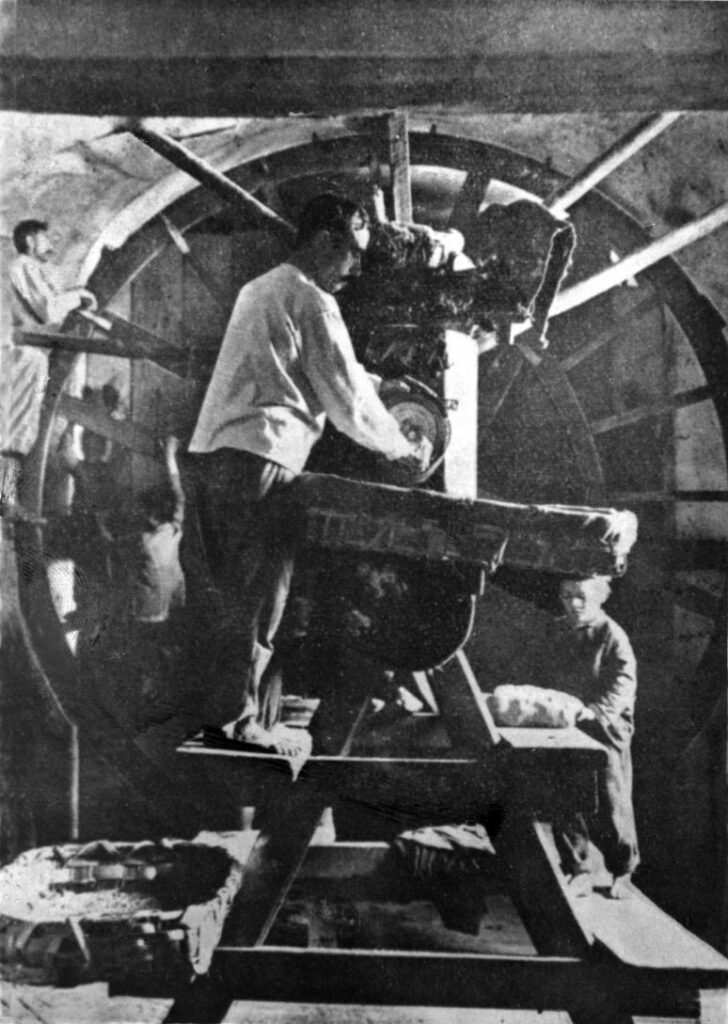

The pasta industry was helped by thirty water mills: some ruins can be admired in the “Valle dei Mulini”. Meanwhile, the textile industry sector entered into crisis and closed definitively in 1783 due to a death of silkworms which blocked the production of silk. Since then, the people of Gragnano dedicated themselves to the "manufacturing of pasta". The golden age of Gragnano pasta is the nineteenth century, years in which large non-family-run pasta factories arose along Via Roma and Piazza Trivione which thus became the center of Gragnano. The pasta factories in fact exhibited macaroni to dry in these streets.

In the middle of the century, production reached its peak: in that period the 75% of the active population worked in the macaroni industry, the pasta factories were more than a hundred and produced over a thousand quintals of pasta a day. Over the centuries, the structural and architectural changes of the city went hand in hand with the production of dry pasta. Via Roma, the symbol of Pasta di Gragnano, was remodeled to favor its exposure to the sun, thus becoming a sort of natural drying room for pasta. Even today it is not difficult to find vintage images that show the yellow-colored road to the bamboo canes placed on trestles that held vermicelli and ziti placed to dry.

The production of "maccaroni" did not slow down after the Unification, on the contrary. After 1861 the pasta factories of Gragnano opened to the markets of cities such as Turin, Florence and Milan. The production of pasta therefore reached its peak. Gragnano even obtained the opening of a railway station for the export of macaroni which connected Gragnano to Naples and therefore to the entire country. On May 12, 1885, King Umberto I and his wife, Queen Margherita of Savoy were present at the inauguration. Later the pasta factories were modernized. Electricity arrived and with it the modern machinery that replaced the ancient hand-operated presses. The twentieth century, however, was a difficult century for the City of Pasta. In the twentieth century the confrontation between the artisanal production of Gragnano and the nascent industry of the north led to a drastic decrease in the Gragnano pasta factories. Those who continued their business focused on quality.

The two World Wars caused the production of Gragnano pasta to enter into crisis, which in the post-war period had to face competition from the great pasta factories of Northern Italy, which had greater capital. The 1980 earthquake aggravated the situation and reduced the number of pasta factories to just eight units. Despite the many problems, Gragnano, thanks to the initiative of the producers and the quality of the product, continues to be the City of Pasta.

Source: Consortium for the Protection of Gragnano Pasta